Sound Theory

The Latinx Sound Cultures Studies webinar series presents Dr. Roberto D. Hernandez and Yaotl Mazahua from Aztlan Underground offer a global perspective on sound. Here we will try to understand Xicanx/Indigenous sounds and music as it emerges as an antagonistic force against the US border. How do we listen to anti-border music’s sonic geographies? How do we tune into anti-border consciousness intimate vocals and instruments? Join us on April 18th at 10 AM PST!

Register via Zoom here: https://ucsb.zoom.us/…/tZcodeuoqDIiGdwS3lpl4D47vAeEr6Kq…

Readings are found here: https://drive.google.com/…/1V…

Soundscaping Memories

The first record of soundscapes presents a collection of micronarratives reflecting on border life. As a juxtaposition of elements, we find the narrative, the soundscape, and the image. The author presents a sensory experience of sounds, moments, places, and objects that hold symbolic meaning for him through a photographic selection. In this way, nature is highlighted as a significant thread, and shows how—in some way, it returns those who seek other horizons. Without realizing it, it comes full circle. Despite the desert’s dominance, they return to where their roots were planted.

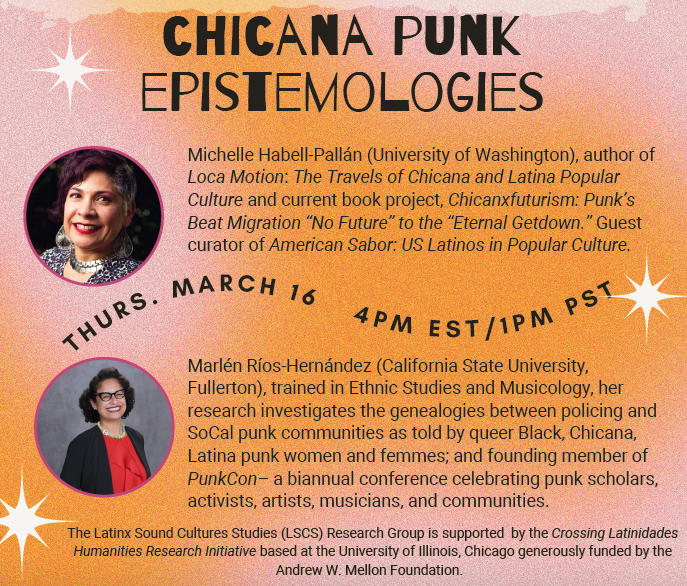

On March 16, 2023, the Latinx Sound Cultures Studies research group (LSCS), supported by the Crossing Latinidades Humanities Research Initiative, hosted a webinar with the presence of Dr. Michelle Habell-Pallán from the University of Washington and Dr. Marlén Ríos-Hernández from California State University, Fullerton discussing the topic “Chicana Punk Epistemologies.”

“The U.S.-Mexican border es una herida abierta where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds. And before a scab forms, it hemorrhages again, the lifeblood of two worlds merging to form a third country—a border culture.”

This quote embodies the profound metaphorical understanding of the border as a wound, a space of constant friction and intersection between cultures. Anzaldúa’s perspective captures the complexity and struggle of living within and between multiple worlds, resonating with the sonic landscape and the multitude of sounds that encapsulate this border culture.

Soundscapes transcend border divisions; they encompass and traverse cities naturally, reaching beyond arbitrary limits. Exploring the identity voice of the border becomes crucial. Many sounds that once echoed are now impossible to capture directly through field recordings. Some sounds can only be preserved through the efforts of individuals who seek to immortalize the essence of things or places over time. Take, for instance, the Rio Bravo. Its thunderous resonance from years past earned it the name “Bravo,” though cartographically labeled as the Rio Grande. Along the Juarez-El Paso border, this river no longer echoes as robustly, nor does it remain ‘Grande’. Its sound, a heritage lost, resides solely in the tales of our ancestors, a fleeting memory slowly fading, much like the once-majestic sound of the Rio Bravo.

The drive to investigate soundscapes stems largely from the avenues it opens when viewed through a rhetorical lens—an interdisciplinary field intersecting phenomenological explorations within the philosophy of sound. Sound studies manifest as an interdisciplinary field, spanning the humanities and social sciences, engaging collaborators from sociology, cultural and media studies, anthropology, cultural history, philosophy, urban geography, and musicology, offering boundless possibilities. However, to comprehensively understand, it’s vital to detail what Soundscapes entail.

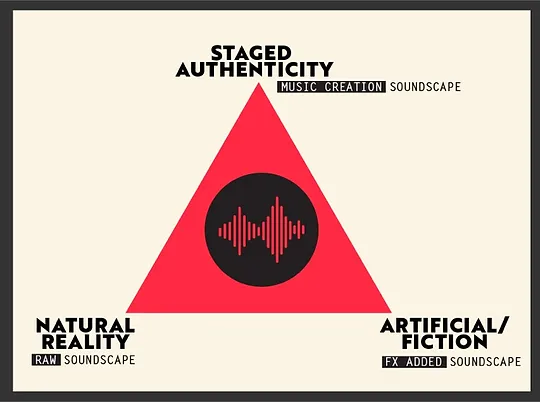

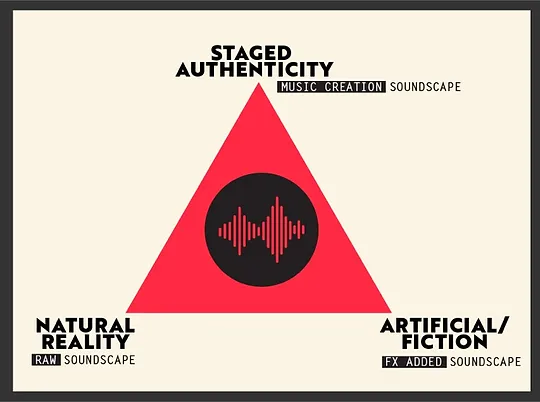

Murray (1997) introduces the concept of Soundscape, a fusion of Sound and Landscape. He defines soundscape as the documentation or capture of an acoustic environment’s sounds. His proposal extends beyond mere audio production, delving into acoustic ecology. Murray underscores the changing soundscape of the world, signaling humanity’s shift toward inhabiting vastly different acoustic environments. This concerns the pollution of sonic spaces and the clamor within diverse habitats. Murray asserts that all sound embodies a soundscape, categorizing every facet of the sonic environment as a field worthy of study.

The soundscape of the US-Mexico border is a symphony of cultural amalgamation, echoing the diversity and complexity of this region. It’s a tapestry woven with the rhythms of languages merging, music intertwining, and narratives colliding. Here, the resonance of footsteps on both sides speaks of shared journeys and unique struggles. The rustle of desert winds carries whispers of hope and hardship, while the languages spoken paint a vivid portrait of heritage and resilience. This auditory landscape is not merely noise but a living testament to the vibrant coexistence of identities, where every sound, from the bustling streets to the tranquil river flow, narrates stories of resilience, adaptation, and the unyielding spirit of a borderland community.

Jose Manuel Flores

Sound aesthetics explores the beauty, perception, and artistic qualities inherent in sound. It delves into the sensory experience of sound, investigating how various elements—such as pitch, timbre, rhythm, and spatial qualities—affect our emotional responses and interpretations. This field embraces the subjective nature of sound, examining how it evokes emotions, shapes narratives, and contributes to our understanding of art, music, film, and the wider sonic environment. Sound aesthetics invites us to explore the intricate interplay between the technical aspects of sound and the profound emotional and aesthetic impact it holds in our lives and artistic expressions. It is well known that sound and semiotics explore the relationship between sound and meaning, focusing on how sound functions as a system of signs and symbols within a cultural or communicative context. For example, Eco (1986) proposed that music’s semiotic system primarily embodies syntax, displaying a structural framework without immediately evident semantic depth. He suggested that deeper semantic significance emerges through interpreting melody as a fusion of sound and lyrics, engaging with notes, vocal or musical expressions, and rhythm. Music encapsulates mathematical values and is delineated through oscillographic or spectrographic measurements depicted on the musical staff. According to Peircean’s theory, musical notes act as symbols representing sounds. In sound design, the musical staff visually mirrors the sounds emitted, establishing a direct correlation between music compositions. On the other hand, there are several authors and scholars who have contributed significantly to discussions and writings about sound aesthetics.

R. Murray Schafer: Known for his work in acoustic ecology, Schafer discusses the aesthetic dimensions of soundscapes and the environmental aspects of sound in his book “The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World.” Jonathan Sterne: A prominent figure in sound studies, Sterne explores the cultural, historical, and technological aspects of sound, including its aesthetics, in works like “The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction” and “MP3: The Meaning of a Format.” Brian Kane: His book “Sound Unseen: Acousmatic Sound in Theory and Practice” explores the aesthetic and philosophical dimensions of acousmatic sound (sound heard without seeing its source), delving into its artistic and perceptual aspects. Salomé Voegelin: Voegelin’s works, including “Listening to Noise and Silence: Towards a Philosophy of Sound Art” and “Sonic Possible Worlds: Hearing the Continuum of Sound,” engage with sound art, aesthetics, and the philosophical implications of sonic experiences. Michael Bull: Author of “Sound Moves: iPod Culture and Urban Experience,” Bull discusses the aesthetic dimensions of everyday sound experiences, particularly in urban environments and mediated through technology. Steven Connor: Known for writings that touch on sound aesthetics among various other topics, Connor has explored the cultural, historical, and philosophical aspects of sound in works like “The Book of Skin” and “Dumbstruck: A Cultural History of Ventriloquism.” These scholars offer diverse perspectives and insights into the aesthetic dimensions of sound, ranging from environmental soundscapes to sonic art, music, and the philosophical implications of auditory experiences.

As a way to analyze sound aesthetics, I rely on the methodological approach “Octadic Model” for the cultural exchanges of Mandoki (2006). Two coordinates are identified; rhetoric and its records; and the dramatic and its modalities. In the first, the registers are lexicon, acoustic, somatic, and scopic. In the second the modalities are proxemic, kinetic, emphatic, and fluxion. Processes of substitution or conversion, equivalence, and continuity in the relationships that the subject establishes with himself, with others, and with his environment through statements that put individual and group identities into play in terms of valorizing (Mandoki, 2006). It speaks of experience and in fact, is the most important, in the sense of social interaction intrinsically associated with sensitivity. The records of Mandoki’s rhetoric are based on the Ciceronian categories, inventio (what is chosen to say), dispositio (the way in which the statement is made), elocutio (how it is presented), memory (what it is linked to), and pronuntiatio or actio (the tone and bearing of the body). From this starting point, the first group is composed to analyze the prosaic established by the registers: lexicon, somatic, acoustic, and scopic.

The channels of exchange of aesthetic statements evident in cinematography are correlated starting with the scopic record that refers to the visual, in this case to the set design, costumes, props, and so on. In this sense, in the film image, interaction can be associated with the way that the message is broadcast and captured by the audience. However, behind this framework operates an articulation and configuration that leads to the connotation and denotation of the message where a semiotic is linked to the aesthetic value through the cinematographic sequences. The somatic register prevails through the corporal display of the actants, their movements, and even their gestures, like a smile that can constitute a facial expression that denotes kindness. The cinematographic image is accompanied by acoustic records such as narration, dialogues, the soundtrack, and the voice-over. On the other hand, the dramatic and its modalities are proxemic, kinetic, emphatic, and fluxion. Mandoki explains that proxemics comes from the Latin proximitas, which means closeness. The term was proposed by Edward Hall to designate the use of space between individuals determined by cultural conventions.

In cinematography, proxemics originate in different ways. One of these is through the different planes and frames, in which the camera movements approach the actants and other elements that make up the photography of the scenes. Another way is through the main medium, the screen, which is where a window of allegorical, metaphorical, and polysemic possibilities that establish proxemics opens up. Intrinsically, the dramatic modality called kinetics is presented. It refers to the dynamism, stability, and solidity of the syntagmas in each record — the camera movements constituted by different planes that look for the contemplative act of hearing. Likewise, it refers to the dynamism in how the different rhetorical figures generated by alliteration are presented, saturated phrases that run through the screen, and that strengthen the message emitted by the scenes. Additionally, the emphatic is noted at the beginning of each plane where musicalization supports the emphatic register and gives intensity and emphasis to the images. In a general way, the dramatic modality of opening or closing through syntagma originates with fluxion. The flow of scenes or planes about the musical sequence marks the entrance and exit of audiovisual discourses. In cinematography, the images flow in such a way that they cross the screen in search of social exchange, an aesthetic exchange. In this sense, we can understand that soundscapes through cinema are a medium with aesthetic approaches where a rhetorical situation is established with the possibility of unleashing a series of meanings, based on the experience of the viewer.

Jose Manuel Flores

Sounds originate from diverse sources—music, noise, and language. In speech, accent quality integrates intensity and tonal quantity. Sound morphology encompasses the structural and organizational facets of sound, involving its configuration, development, and attributes within temporal or spatial contexts.

Inherent to sound, the syllable serves as a foundational unit composed of phonemes, engaging two consecutive sound perceptions and muscular actions. Additionally, phonic groups are situated amid pauses, segregating sounds within intervals of silence. Applied within the domain of sound studies, soundscape morphology focuses on modifications within sound groups, arranged similarly in time or space. Despite sound’s invisibility, its essence can be captured using technology. Spectrograms or waveforms translate sound into visual depictions, facilitating a detailed examination of its morphology. This analysis unveils essential physical attributes like pitch, duration, intensity, and timbre.